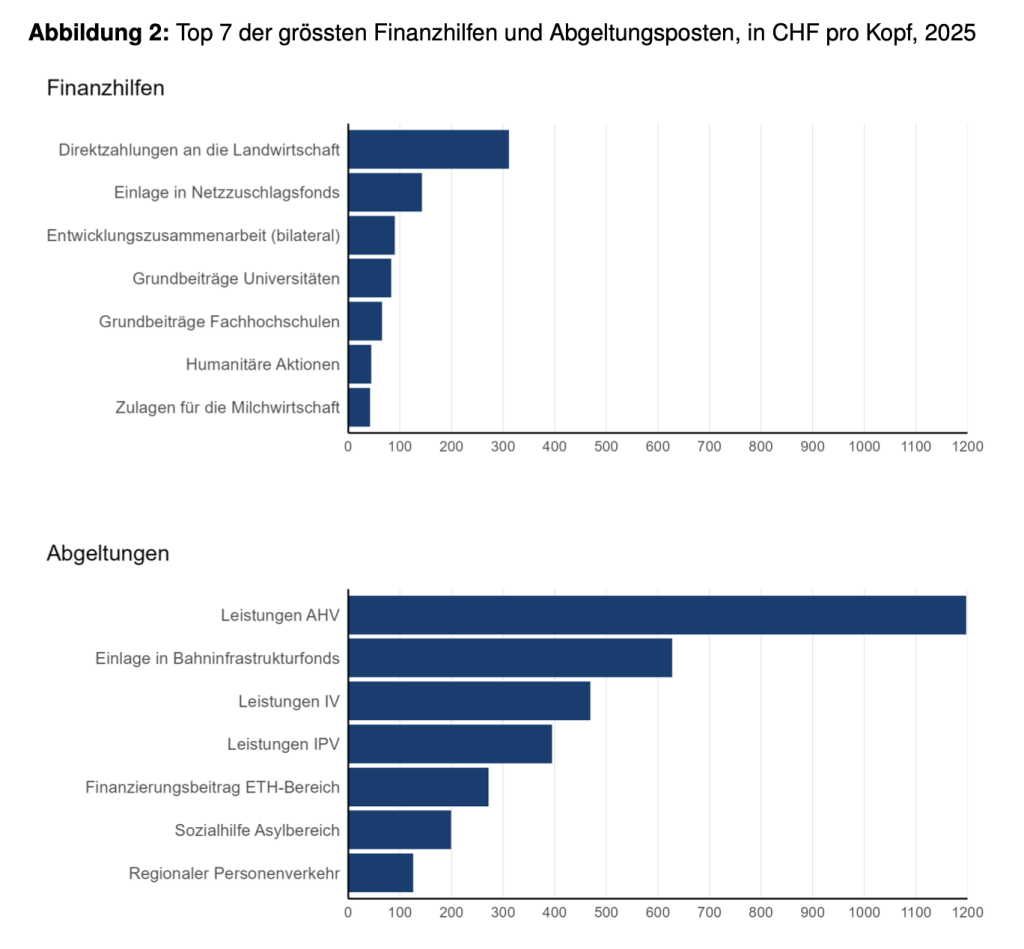

Subsidies in Switzerland

A new report by the Institut für Schweizer Wirtschaftspolitik describes who receives them. Report (in German).

“Frontiers of Digital Finance,” CEPR, 2025

CEPR eBook, 12 November 2025. PDF, HTML.

VoxEU column: Frontiers of Digital Finance: A Global Perspective. HTML.

VoxEU column: Frontiers of Digital Finance: Stablecoins, monetary ‘singleness’, tokenisation, and decentralised finance. HTML.

My introduction to/summary of the book:

The digitisation of payment, trading, and settlement systems is reshaping the financial architecture. New technologies are transforming how value is created, stored, transferred, and accounted for, altering the balance between public and private money, enabling the bundling of services, challenging traditional financial institutions, and prompting a wave of regulatory and institutional responses.

The global picture is uneven. Some regions are leapfrogging others, and conflicting ideologies about the proper role of the state in money give rise to fragmentation and concerns about monetary sovereignty.

This book offers an overview of major trends, as analysed by leading researchers and policymakers. It is structured in four parts. Part 1 presents regional perspectives, examining the approaches taken by India, Brazil, sub-Saharan Africa, the United States, and the euro area. For the euro area, the focus is on the digital euro and its implications for monetary sovereignty, privacy, and holding limits aimed at preserving financial stability.

Part 2 delves into stablecoins – the shooting stars in the digital financial ecosystem. Their evolution has spurred a flurry of policy debate, with the European Union’s Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR) and the US GENIUS Act now offering greater regulatory clarity.

Part 3 turns to the concept of monetary ‘singleness’ – the principle that all forms of money in a currency area should be fully interchangeable and trade at par. As new digital forms of money proliferate, the cohesion of the monetary system may be called into question.

Part 4 brings together chapters on tokenisation, digital platforms, and decentralised finance (DeFi), and their broader impact on service bundling, credit allocation, financial inclusion, and consumer protection.

Regional perspectives

In the opening chapter of Part 1, Amiyatosh Purnanandam describes how India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI), launched in 2016, has improved the efficiency of account-based payment systems by addressing the core frictions of information exchange, authentication, and final settlement. Developed under a public-private partnership, UPI enables real-time, low-cost, and interoperable digital payments between any two entities, regardless of their bank or payment service provider. India overcame challenges around identity verification and financial inclusion by implementing a nationwide system of digital, biometric-based identification and by expanding access to bank accounts for large segments of the unbanked population. These developments, alongside digital infrastructure investments and regulatory support for private sector participation, allowed UPI to lower transaction costs and provide small businesses with digital transaction histories that improved access to credit.

Purnanandam highlights how demonetisation and the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of UPI. The system’s interoperable design allows users to choose among competing apps, reinforcing network effects and encouraging innovation. Early adoption by banks in some areas led to persistent increases in digital payment usage. Moreover, UPI has enabled streamlined welfare disbursements, with nearly 60% of subsidy payments being delivered directly into beneficiary accounts by 2024. According to Purnanandam, the UPI experience demonstrates the critical role of coordinated efforts across public and private sectors, along with a flexible and inclusive regulatory framework.

Fabio Araujo and Arnildo da Silva Correa describe the Central Bank of Brazil’s comprehensive innovation strategy, Agenda BC#, fostering tokenisation and integration to enable faster, more transparent, and programmable asset transfers. The agenda is built around four interlinked pillars: (1) Pix, an instant payment system launched in 2020, which also supports a ‘synthetic’ retail central bank digital currency (CBDC) model; (2) Open Finance, which promotes secure data sharing and competition; (3) Drex, Brazil’s central bank digital currency designed as a platform for a tokenised economy; and (4) the internationalisation of the Brazilian real, through regulatory modernisation and cross-border interoperability. Each component reinforces the others, creating a cohesive, digital financial ecosystem that enhances efficiency, security, innovation, and inclusivity.

Pix marked the foundational shift, offering a public infrastructure for instant, programmable payments that has been widely adopted across Brazil and credited with improving financial inclusion and spurring innovation. Open Finance expanded the ecosystem by allowing consumers to share financial data among institutions, unlocking more tailored services and competitive offerings. Drex builds on this by introducing distributed ledger technology, enabling advanced programmability, atomicity, and secure, tokenised deposits while incorporating privacy safeguards such as zero-knowledge proofs. Finally, internationalisation efforts are aligning domestic systems with global standards. Together, these initiatives aim to create a user-centric financial system where services are accessed through intelligent aggregators, enhanced by AI and driven by user-controlled data.

Luca Ricci and co-authors describe how digital innovations are reshaping the payment landscape across sub-Saharan Africa, facilitating financial inclusion, payment efficiency, lower remittance costs, and reduced informality. Private mobile money has been particularly impactful, with account ownership far outstripping the growth of traditional bank accounts. While central bank digital currencies, fast payment systems, and crypto assets are debated (with Nigeria having already launched the eNaira), their broader adoption is held back by weak digital infrastructure, limited institutional capacity, low levels of financial and digital literacy, and the high costs of system deployment. Cross-border payments remain slow and costly, and fragile governance frameworks heighten concerns about consumer protection, data privacy, and financial integrity.

To address these challenges, the authors outline four policy priorities: (1) investment in infrastructure and skills; (2) supporting private innovation within secure and competitive regulatory frameworks that enable interoperability and reinforce governance; (3) positioning public digital tools to complement – rather than compete with – private solutions, based on assessments of market gaps and resource needs; and (4) fostering regional and international coordination to ensure interoperability and resilience. Ultimately, digital payment reforms must be anchored in sound macroeconomic policies that preserve monetary sovereignty and financial stability.

Michael Lee argues that the 2025 Executive Order on digital financial technology and the GENIUS Act represent a strategic shift in the United States towards private sector-driven innovation in blockchain-based financial systems. The Executive Order rules out the development of a CBDC while endorsing a technology-neutral approach and regulatory clarity for stablecoins. The GENIUS Act establishes a federal framework for fiat-backed payment stablecoins, mandating at-par redemption, backing primarily by US dollar cash and cash equivalents, and regulatory oversight. Regarding the more than 340 stablecoins in circulation – 97% dollar-denominated and dominated by Tether and Circle – concerns remain over reserve transparency, and redemption practices vary widely.

Beyond stablecoins, Lee describes the increasing tokenisation of Treasury funds and commercial bank deposits. Tokenised US Treasury funds are largely held by long-term investors or used as on-chain reserves. Deposit tokens and tokenised deposits typically align with existing regulatory standards – including full know-your-customer (KYC)/anti-money laundering (AML) compliance and access via whitelisting – and can pay interest. In contrast, stablecoins circulate more freely (issuers functionally manage a whitelist only at the issuance stage) but are barred from offering interest directly under the GENIUS Act; however, issuers often partner with platforms to indirectly deliver yield. Together, these instruments form a spectrum, each balancing accessibility and return in different ways.

Ulrich Bindseil and Piero Cipollone argue that central bank electronic cash (CBEC) is essential to preserving monetary sovereignty, as private (often foreign) service providers increasingly dominate retail payments. This carries significant risks: rising payment costs due to oligopolistic market power, reduced financial and monetary stability, loss of seignorage income, and increased vulnerability to geopolitical risks. Bindseil and Cipollone present CBEC not as a disruption but as a necessary evolution to ensure the continued public provision of a neutral, secure, and sovereign monetary instrument that is designed to complement rather than replace commercial bank money.

The authors emphasise that monetary sovereignty faces new threats from globalisation, the advent of new technologies such as public blockchains, and a surge of nationalism that dismisses the merits of international co-operation. CBEC helps counter these threats across five dimensions: it protects macro-financial stability by preventing dollarisation; it ensures access to payment systems without abuse of market power; it preserves seigniorage income and the financial independence of central banks; it reduces strategic dependencies on foreign actors; and it protects informational sovereignty by avoiding overreliance on foreign-owned platforms.

Maarten van Oordt argues that the accelerating shift away from cash in the euro area is driving a significant erosion of privacy in payments. Unlike cash, electronic payments generate detailed records that are monitored by payment service providers and subjected to regulatory oversight. These data are not only used for compliance but also for commercial purposes, and they can be leveraged not just to monitor but also to censor or exclude individuals. The author emphasises that common justifications for payment surveillance – such as crime prevention and tax enforcement – do not automatically warrant broad monitoring powers in a democratic society.

Van Oordt does not expect the currently proposed digital euro design, which includes both online and offline payment options, to close the growing ‘privacy gap’ in retail payments. Online digital euro payments would be processed centrally, offering little improvement over existing systems, and, depending on the robustness of pseudonymisation techniques, could even exacerbate privacy risks. Offline payments, while potentially more private, face challenges such as usage limits and unresolved security concerns. Without critical amendments – such as enabling remote payments through offline balances or designing online payments to emulate the anonymity of cash – the author foresees the digital euro as heightening surveillance risks. He stresses that privacy in payments is a public good and warns that failing to safeguard it in the digital age would squander a crucial opportunity to redesign the financial system in such a way that upholds individual autonomy and democratic values.

Katrin Assenmacher and Oscar Soons explain that the European Commission’s June 2023 legislative proposal tasks the European Central Bank (ECB) with developing instruments to limit the use of the digital euro as a store of value, including the introduction of individual holding limits. These limits are intended to balance three objectives: enabling convenient payments; ensuring smooth monetary policy transmission; and safeguarding financial stability. The authors describe the ECB’s methodology for calibrating these limits so they are high enough for payment use but low enough to prevent significant bank deposit outflows that could destabilise funding structures.

To assess the appropriate holding limits, the ECB considers both a business-as-usual scenario – where the digital euro is mainly used for payments – and a flight-to-safety scenario, which involves mass withdrawals from banks during crises. Surveys and econometric analyses yield a broad range of estimates for digital euro demand. However, even under conservative assumptions, research indicates that large deposit outflows would likely only arise if individual holding limits exceeded €5,000, at which point banks would need to rely more heavily on central bank or market-based funding to manage liquidity pressures.

Stablecoins

In the first chapter of Part 2, Hugo van Buggenum, Hans Gersbach, and Sebastian Zelzner discuss how stablecoins – digital assets pegged to fiat currencies – have rapidly evolved from niche instruments into a major segment of digital finance. While fiat-backed stablecoins promise to combine the technological advantages of crypto with the stability of traditional money, depegging episodes underscore their vulnerability to run risks due to illiquid reserves, limited issuer commitment, and noisy market signals. Trading on active secondary markets can mitigate run incentives by giving holders alternative exit options when redemptions are restricted.

The authors discuss how the EU MiCA Regulation and the US GENIUS Act address systemic risks posed by stablecoins, focusing on reserve quality, redemption rights, and transparency. They suggest that well-designed redemption restrictions – such as gates or fees – should be permitted to prevent destabilising runs. They also caution against the remuneration of stablecoins, as interest payments could trigger destabilising competitive dynamics and coordination failures across issuers, and examine potential effects on banks, monetary policy transmission, and overall financial stability.

Rodney Garratt highlights the dramatic growth of the US dollar-denominated stablecoin market and the fundamental regulatory shift that now encourages institutional participation, including by commercial banks. The author expects the entry of traditional financial institutions to reshape the competitive landscape, with banks serving their regulated clients via public blockchain-based payment rails, while existing issuers continue to operate within the crypto ecosystem.

Garratt likens stablecoins to digital travellers’ cheques – clearing instruments redeemable at par but not tied to individual account holders. As banks enter the space, redemption frictions and interoperability challenges echo historical issues from the pre-clearinghouse era of cheque processing. He argues that a universal stablecoin clearing system will be crucial for broader adoption, ensuring fungibility and monetary singleness across issuers. While stablecoins may not offer clear advantages in many domestic use cases – given the rise of real-time payment systems – he sees potential in global, programmable transactions, particularly for corporate users needing low-cost, high-speed, cross-border payments. Garratt predicts bank-issued stablecoins will have short lifecycles, acting as temporary payment instruments rather than long-term stores of value.

Steve Cecchetti and Kermit Schoenholtz compare stablecoins and tokenised deposits within the context of the new US regulatory framework. They note that although the GENIUS Act prohibits interest payments to holders, limits eligible reserve assets, and enforces compliance with KYC, AML, and anti-terrorist financing (ATF) standards, it still contains significant regulatory gaps. Platforms can circumvent the interest ban by offering yield-like ‘rewards’; reserve requirements permit exposure to run-prone assets like prime money market funds and uninsured bank deposits; and enforcing illicit-use restrictions is particularly challenging for users of noncustodial wallets. Most notably, the absence of capital requirements raises doubts about the ability of stablecoins to serve as safe, information-insensitive assets under stress.

According to the authors, tokenised bank deposits offer a more stable and robust alternative, combining the legal protections of traditional bank deposits with features such as programmable settlement, real-time clearing, and blockchain interoperability. Because they are issued by regulated, FDIC-insured banks with central bank access, tokenised deposits are shielded from many of the structural vulnerabilities that afflict stablecoins. Moreover, they offer stronger privacy protections, reduce cross-border redemption risks, and more easily support multiple currencies – mitigating concerns around dollar dominance.

David Andolfatto explores the role of Tether (USDT) in the evolving landscape of private digital money, highlighting both its utility and its vulnerabilities. Pegged to the US dollar while operating outside the traditional banking system, Tether fills critical roles in blockchain-based asset trading, cross-border payments, and as a dollar substitute in emerging markets. While verified institutional users are entitled to par redemption, retail users depend on secondary market liquidity. This two-tier structure and the absence of regulatory oversight raise financial stability concerns.

Despite claims of full reserve backing, primarily in short-term US Treasuries, Tether’s transparency is limited to attestations, and it is legally structured to avoid US regulation. But Andolfatto argues that Tether’s reliance on Cantor Fitzgerald, a US-regulated primary dealer, presents a policy window for oversight and systemic risk mitigation. In particular, US policymakers could require Cantor to act as a fiduciary, using its Federal Reserve master account to tighten reserve management, and applying existing AML/KYC standards.

Richard Portes argues that the multi-issuer stablecoin model (MISC), where a stablecoin is issued jointly by EU-regulated institutions and third-country entities, presents serious financial stability risks and regulatory challenges. This arrangement, not explicitly foreseen under the MiCA regulation, creates loopholes for regulatory arbitrage, fragmented reserve management, and accountability confusion, particularly during redemption runs or crises. The fungibility of tokens across jurisdictions allows issuers and holders to treat them as interchangeable, even though only part of the system is subject to EU rules, reserves may be ringfenced abroad during stress, and redemptions could be unequally honoured.

Portes sees several policy options, including banning MISCs outright, amending MiCA to explicitly regulate cross-jurisdiction co-issuance, or developing global regulatory standards. He notes that some EU policymakers have voiced strong opposition to MISCs, and warns that regardless of the legislative path chosen, urgent supervisory and legal adaptations are needed to preserve financial stability, close regulatory gaps, and uphold MiCA’s credibility in a globalised crypto-financial system.

Harald Uhlig compares European plans for a CBDC and the US strategy to promote privately issued stablecoins. While the ECB sees CBDC as a way to modernise cash, preserve monetary sovereignty, and reduce dependence on foreign payment providers, the US approach possibly reflects stronger trust in markets and concerns about government overreach and privacy. Despite these different strategies, the author notes a fundamental convergence: both digital currencies must avoid paying interest and may ultimately rely on central bank backing to ensure safety and stability.

Uhlig is critical of the US regulatory framework that prevents stablecoins from becoming robust and competitive – particularly the denial of Federal Reserve master accounts and interest payments, which would allow them to operate like fully reserved narrow banks. He warns that this creates stablecoins that are ‘fragile by design’, as illustrated by recent depegging events. He also highlights the inconsistency of paying interest on bank reserves but not on digital cash held by the public, viewing it as a concession to the traditional banking sector. While stablecoins may offer innovative features like smart contracts and programmable payments, their growth could generate international tensions. Ultimately, Uhlig sees stablecoins and CBDCs as part of ongoing creative destruction in finance – technological progress that doesn’t eliminate but instead relocates deeper structural tensions like liquidity risk and maturity mismatches.

Monetary singleness

In the first chapter of Part 3, Rhys Bidder explores the principle of singleness of money – the idea that all forms of money within a currency area, including bank deposits and digital tokens, should trade at par with the central bank’s unit of account. In the traditional two-tier banking system, singleness is maintained through central bank infrastructure and liquidity support, ensuring trust and stability. In contrast, stablecoins and DeFi instruments operate outside these systems, making minor deviations from par common.

Bidder argues that these small fluctuations are not inherently problematic and may fade as technology, transparency, and market infrastructure improve. The real concern lies in large depegs during periods of stress, such as during the 2023 US banking crisis, which exposed the fragility of stablecoins under liquidity pressure. To address this, he proposes that stablecoins backed by high-quality assets be granted conditional access to emergency liquidity facilities. Rather than fixating on minor price noise, the policy debate should focus on preventing systemic instability during times of stress.

Jonathan Chiu and Cyril Monnet similarly examine the concept of monetary singleness. Their starting point is the common concern among central banks that programmable digital currencies – whose use can be restricted through embedded rules – could undermine singleness by creating distinctions among tokens of equal face value. This concern has led central banks to dismiss digital currencies incorporating programmability. In contrast, the authors argue that programmability can enhance economic efficiency and that the loss of singleness may be an acceptable – or even desirable – feature in certain contexts.

Chiu and Monnet observe that, under perfect information, token prices would adjust to reflect differences in restrictions, enabling efficient allocations despite the loss of singleness. In such cases, prohibiting programmability would reduce welfare. However, under imperfect information, adverse selection may arise, with unrestricted tokens effectively subsidising restricted ones. As these distortions grow, the welfare gains from programmability diminish. The authors challenge the conventional view – often informed by the US free banking era – that non-uniform money necessarily leads to inefficiency. Instead, they advocate for a nuanced regulatory approach, such as Pigouvian taxes on excessive programmability or incentives to enhance token transparency.

Tokenisation, platforms, credit, and decentralised finance

In the first chapter of Part 4, Jon Frost, Leonardo Gambacorta, Anneke Kosse, and Peter Wierts argue that tokenisation – the digital representation of assets on programmable platforms – has the potential to improve the efficiency and functionality of the financial system. The tokenisation of money, including central bank money and commercial bank deposits, could be a first step, while stablecoins fall short in the authors’ eyes on stability, liquidity, and regulatory compliance. They suggest building on the existing two-tier monetary system and integrating tokenisation with central bank money to ensure trust and safety.

The authors also see potential for tokenisation to enhance capital markets – particularly in bond issuance – by reducing costs and improving liquidity. However, they also point to risks stemming from legal uncertainty, operational vulnerabilities, and the concentration of multiple functions on single platforms. Governance challenges and poor interoperability with legacy systems further complicate adoption. In the authors’ view, both public and private sectors have roles to play in managing these risks and enabling tokenisation to contribute meaningfully to financial safety and efficiency.

Emre Ozdenoren and Kathy Yuan explore how tokenised money – digital currencies issued or guaranteed by central banks or private platforms – can transform financial systems by automating transactions, reducing information frictions, and enhancing liquidity. Unlike traditional digital payment instruments, tokenised money incorporates smart contracts, enabling automatic enforcement of contractual terms without intermediaries. It serves a dual function as both a payment method and a collateral asset for financial contracts, offering greater efficiency, security, and traceability. Its programmability reduces human error, minimises fraud, and lowers custodial and settlement costs, particularly in complex financial transactions involving future obligations.

Ozdenoren and Yuan describe how tokenised money acts as a collateral multiplier, expanding the supply of secure and transparent assets while reducing reliance on sovereign bonds – thereby mitigating systemic risks such as the ‘dash for cash’ or the sovereign-financial doom loop. Tokenisation also enables the creation of secondary markets, closely integrating funding and market liquidity. While it introduces new risks, including cybersecurity threats and novel financial vulnerabilities, its potential benefits – and seigniorage opportunities for issuers – position tokenised money as a foundational element of future financial infrastructure.

Markus Brunnermeier and Jonathan Payne similarly stress the role of digital payment ledgers in offering a powerful new mechanism to expand access to credit by embedding repayment directly into digital transaction systems. Turning future revenues into ‘digital collateral’, these systems promise to relax borrowing constraints, but their potential is shaped less by technology than by institutional design and confronts a trilemma: no arrangement can simultaneously ensure strong enforcement, limit private rent extraction, and preserve user privacy. According to the authors, this trilemma lies at the heart of the evolving financial architecture.

Brunnermeier and Payne compare three institutional approaches. The first is BigTech platforms, which can enforce repayment by controlling trade and payment flows, using proprietary tokens and internal ledgers, but create risks of monopoly power and privacy loss. The second is public options – from basic infrastructure like FedNow to full programmable CBDCs – that can serve as inclusive, transparent alternatives, but may weaken enforcement or require trade-offs on privacy. The third approach is regulatory ‘co-opetition’ between platforms, which encourages enforcement through shared data and coordinated default tracking, while using competition to suppress rents. All these models face technical and governance complexities, particularly in enforcing privacy and limiting systemic risk. The authors conclude that, ultimately, expanding access to credit through digital payment systems demands a nuanced balance across enforcement, rent extraction, and privacy.

Wenqian Huang describes how DeFi is transforming financial infrastructure by enabling trading and lending without traditional intermediaries. At the core of this system are decentralised exchanges and lending protocols that use smart contracts to automate market functions. Decentralised exchanges replace order books with pooled liquidity and algorithmic pricing, enabling large trades with minimal price dislocation for near-par instruments like stablecoins. DeFi lending protocols mimic collateralised finance by letting users borrow against tokenised assets, with automatic margin calls enforced by code. These innovations are now expanding into real-world asset markets, such as tokenised real estate.

Huang argues that the integration of DeFi mechanisms into tokenised real-world asset markets offers efficiency gains but also introduces risks. As DeFi becomes increasingly intertwined with fiat systems and real assets, the challenge for regulators is to craft oversight that acknowledges decentralisation while mitigating systemic risk. Ultimately, DeFi’s contribution may not lie in replacing existing institutions but in reshaping our understanding of resilient and efficient market design.

Claudio Tebaldi argues that digital adoption, rising incomes, and growing global interest have brought a younger, more diverse cohort of retail investors into financial markets. While these investors now access a broad range of complex financial products, their financial literacy is often low and their understanding of product risks inadequate. De facto, digital innovation brings with it a form of technology-driven deregulation, and finding the right balance between fostering innovation and protecting retail investors is difficult. While some regulatory environments, such as that of the European Union, emphasise consumer protection through rules and oversight, they often limit scalability and participation, raising concerns about accessibility and innovation. In some cases, platform design – rather than regulation – bears the burden of educating and guiding users.

Tebaldi proposes a regulatory framework that balances the goals of consumer protection, large-scale participation, and inclusive stakeholder governance. He argues that AI-powered robo-advisory tools offer promise in bridging the education gap at scale. To improve governance, token issuers should meet governance standards comparable to those common in traditional finance.

“CBDC and Monetary Architecture,” UniBe DP, 2025

UniBe VWI Discussion Paper 25-09, October 2025. PDF.

We review the macroeconomic literature on retail central bank digital currency (CBDC), organizing the discussion around a CBDC-irrelevance result. We identify both fundamental and policy-related sources of relevance, or departures from neutrality. Bank disintermediation—the crowding out of deposits—does not, by itself, constitute such a source. We argue that the literature has primarily focused on policy-related sources of non-neutrality, often without making this focus explicit. From a macroeconomic perspective, CBDC is, at its core, a matter of monetary architecture, and political economy considerations are central to understanding CBDC policy design.

“Macroeconomics II,” Bern, Fall 2025

MA course at the University of Bern.

Time: Monday 10:15-12:00. Location: UniS A-126. Uni Bern’s official course page. Course assistant: Noah Köhli.

The course introduces Master students to modern macroeconomic theory. Building on the analysis of the consumption-saving tradeoff and on concepts from general equilibrium theory, the course covers workhorse general equilibrium models of modern macroeconomics, including the representative agent framework, the overlapping generations model, and the Lucas tree model.

Lectures follow chapters 1–4 (possibly 5) in this book.

“Makroökonomie I (Macroeconomics I),” Bern, Fall 2025

BA course at the University of Bern, taught in German.

Time: Monday 14:15-16:00. Location: H4 201. Uni Bern’s official course page. Course assistant: Sally Dubach.

Course description:

Die Vorlesung vermittelt einen ersten Einblick in die moderne Makroökonomie. Sie baut auf der Veranstaltung „Einführung in die Makroökonomie“ des Einführungsstudiums auf und betont sowohl die Mikrofundierung als auch dynamische Aspekte. Das heisst, sie interpretiert makroökonomische Entwicklungen als das Ergebnis zielgerichteten individuellen (mikroökonomischen) Handelns, und sie wird der Tatsache gerecht, dass wirtschaftliche Entscheidungen Erwartungen widerspiegeln und Konsequenzen in der Zukunft haben. Der klassische Modellrahmen, der in der Vorlesung entwickelt wird, bietet die Grundlage für die Analyse von Wachstum, Konsum, Arbeitsangebot, Investitionen oder Geld- und Fiskalpolitik sowie vieler anderer Themen, die auch in anderen Veranstaltungen des BA Studiums und darüber hinaus behandelt werden.

The course closely follows Pablo Kurlat’s (2020) textbook A Course in Modern Macroeconomics (book website). Lecture notes are available here. Several sections in the lecture notes are not covered in class and are not relevant for the exam. The syllabus distributed by Sally Dubach contains further details.

“A Tractable Model of Epidemic Control and Equilibrium Dynamics”, JEDC, 2025

With Martín Gonzalez-Eiras. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 178, 105145. September 2025. PDF, PDF of appendices C, D, E.

We develop a single-state model of epidemic control and equilibrium dynamics, and we show that its simplicity comes at very low cost during the early phase of an epidemic. Novel analytical results concern the continuity of the policy function; the reversal from lockdown to stimulus policies; and the relaxation of optimal lockdowns when testing is feasible. The model’s enhanced computational efficiency over SIR-based frameworks allows for the quantitative assessment of various new scenarios and specifications. Calibrated to reflect the COVID-19 pandemic, the model predicts an optimal initial activity reduction of 38 percent, with subsequent stimulus measures accounting for one-third of the welfare gains from optimal government intervention. The threat of recurrent infection waves makes the optimal lockdown more stringent, while a linear or near-linear activity-infection nexus, or strong consumption smoothing needs, reduce its stringency.

“Liquidity Crisis Support made in Switzerland and the Too-big-to-fail Subsidy,” VoxEU, 2025

VoxEU, June 30, 2025. With Cyril Monnet and Remo Taudien. HTML.

From the text:

To judge the incentive effects of a public liquidity backstop framework, ideally one would assess its contribution to the overall too-big-to-fail subsidy. However, isolating this contribution is empirically challenging. To estimate the broader too-big-to-fail subsidy, we conduct a quantitative analysis based on the industry-standard CreditGrades framework (Merton 1974, Finkelstein et al. 2002). Using publicly available data for 2022 and applying conservative assumptions about recovery rates and asset volatility, we estimate that UBS Group AG benefited from an annual senior debt subsidy of approximately $2.9 billion–somewhat below the range reported in comparable studies.

This finding underscores the need for a regulatory framework that effectively addresses the incentive distortions created by such subsidies. Any meaningful solution should adopt a holistic approach, targeting the combined consequences of too-big-to-fail status. Crucially, corrective measures should operate ex-ante –targeting the incentives of current management and shareholders–rather than relying on punitive conditions imposed during a crisis. Ex-post penalties risk undermining the resolution process (‘throwing out the baby with the bathwater’) and may lack political feasibility in the face of imminent failure. Importantly, and contrary to the approach outlined in the Swiss proposal, effective regulation must also be independent of a bank’s current financial performance, which reflects past decisions and random shocks rather than the decisions that regulation seeks to influence.

“Pricing Liquidity Support: A PLB for Switzerland”, CEPR DP, 2025

With Cyril Monnet and Remo Taudien. CEPR Discussion Paper 20309, May 2025. PDF.

The proposed revision of the Swiss Banking Act introduces a public liquidity backstop (PLB) for distressed systemically important banks (SIBs), in part to facilitate resolution. We examine the impact of the PLB on fiscal balances, welfare, and the incentives of bank shareholders and management. A PLB, like too-big-to-fail (TBTF) status, acts as a subsidy for non-convertible bonds, which can create negative externalities. Corrective measures should be implemented before the PLB is activated to align incentives with societal interests. We conservatively estimate that UBS Group’s TBTF status results in funding cost reductions of at least USD 2.9 billion in 2022. The risk for Switzerland of hosting SIBs warrants additional precautionary savings.

VOCES8: Agnus Dei by Samuel Barber

“Macro Finance: Assets, Government Debt, and Cryptos,” Bern, Spring 2025

BA course at the University of Bern.

Time: Monday, 10:15–12:00. Location: H4, 106. Uni Bern’s official course page.

This course is aimed at students interested in macro finance who have completed their mandatory training in microeconomics, macroeconomics, and mathematics. Macro finance focuses on the pricing of securities and other assets. Using the Euler equation as a basis, we derive the fundamental pricing relationships. The course then explores a range of applications, including bubbles, government debt, money, the interaction between fiscal and monetary policy, CBDCs, and crypto assets. Grades may be based on class participation, group work and presentations, and/or a written exam.

“Fiscal and Monetary Policies,” Bern, Spring 2025

MA course at the University of Bern.

Lecture: Monday, 12.15 – 14.00, UniS A027.

Session: Tuesday, 12.15 – 14.00, UniS A017, on 4 Mar, 18 Mar, 25 Mar, 15 Apr, 29 Apr, 20 May. Some lecture and session dates may be swapped.

Uni Bern’s official course page. Problem sets and solutions can be found here.

The course covers macroeconomic theories of fiscal policy (including tax and debt policy) and the interaction between fiscal and monetary policy. Participants should be familiar with the material covered in the course Macroeconomics II. The course grade reflects the final exam grade. The classes follow selected chapters in the textbook Macroeconomic Analysis (MIT Press, 2019) and build on the material covered in the Macroeconomics II course, which follows the same text.

Main contents:

- Concepts.

- RA model with government spending and taxes.

- Government debt in RA model.

- Government debt and social security in OLG model.

- Neutrality results.

- Consolidated government budget constraint.

- Fiscal effects on inflation. Game of chicken.

- FTPL. Active and passive policies.

- Tax smoothing.

- Time consistent policy.

- Sovereign debt.

Does the US Administration Prohibit the Use of Reserves?

An executive order issued on January 23, 2025, aims at protecting “Americans from the risks of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), which threaten the stability of the financial system, individual privacy, and the sovereignty of the United States, including by prohibiting the establishment, issuance, circulation, and use of a CBDC within the jurisdiction of the United States.”

The executive order defines CBDC as “a form of digital money or monetary value, denominated in the national unit of account, that is a direct liability of the central bank.”

As (a reader of) Matt Levine’s newsletter points out, the two statements combined have wide ranging implications. Reserves, which are issued by the Fed and which banks use to pay each other, are a form of digital money; they are denominated in the national unit of account; and they are a direct liability of the central bank. So, their issuance and use is prohibited now. This would mean the end of the monetary architecture as we know it. Or, the executive order was just not carefully drafted.

Unlike in the executive order, retail CBDC is typically defined as “reserves for all,” that is digital; in the national unit of account; a direct liability of the Fed; and ACCESSIBLE TO EVERYBODY rather than just banks. Prohibiting CBDC as typically understood would not be as wide ranging, but still not necessarily a good idea. As Morten Bech has pointed out, CBDC = MM0GA or

CBDC = make M0 great again.

HT to Beatrice Weder di Mauro.

“Pricing Liquidity Support: A PLB for Switzerland”, UniBe DP, 2025

With Cyril Monnet and Remo Taudien. University of Bern Discussion Paper 25.01, January 2025. PDF.

The proposed revision of the Swiss Banking Act introduces a public liquidity backstop (PLB) for distressed systemically important banks (SIBs), in part to facilitate resolution. We examine the impact of the PLB on fiscal balances, societal welfare, and the incentives of bank shareholders and management. A PLB, like too-big-to-fail (TBTF) status, acts as a subsidy for non-convertible bonds, which can create negative externalities. Corrective measures must be implemented before the PLB is activated to align incentives with societal interests. We conservatively estimate that Swiss SIBs’ TBTF status results in funding cost reductions far greater than the proposed ex-ante compensation, with UBS Group AG alone gaining at least USD 2.9 billion in 2022. The risk for Switzerland of hosting SIBs warrants additional precautionary savings.

“Report by the Parliamentary Investigation Committee on the Conduct of the Authorities in the Context of the Emergency Takeover of Credit Suisse”

The report (in German). From the press release:

The Parliamentary Investigation Committee (PInC) attributes the Credit Suisse crisis to years of mismanagement at the bank. It is critical of FINMA’s relaxation of capital requirements and regrets the lack of effectiveness of its banking supervision. The PInC also criticises the hesitant development of the TBTF legislation and identifies shortcomings in the flow of information between authorities. It does not find any misconduct on the part of the authorities as a causative factor in the Credit Suisse crisis and acknowledges that the authorities prevented a global financial crisis in March 2023. In its report, however, the PInC calls for specific improvements: a more international approach to TBTF regulations, more effective rules for systemically important banks, and clearer directives on coordination with the authorities responsible for financial stability in Switzerland.

… the Federal Council and Parliament gave too much consideration to the concerns of systemically important banks (SIBs) in the implementation of international standards (Basel III, BCBS and FSB principles), particularly from 2015 on. For example, the Federal Council repeatedly granted SIBs extended transitional periods to comply with further legal developments; it also suggested delaying the adoption of international standards. The PInC believes the Federal Council acted too hesitantly, particularly with regard to the introduction of a public liquidity backstop (PLB).

The PInC also scrutinised FINMA’s conduct of business, finding that its supervisory activities – while intensive – lacked sufficient impact. Despite numerous enforcement proceedings and warnings issued by FINMA, Credit Suisse continued to be plagued by a series of scandals. The PInC finds it regrettable that FINMA did not opt for a withdrawal of recognition for guarantees of proper business conduct during this period.

Moreover, the PInC fails to understand why FINMA granted Credit Suisse extensive easing of its capital adequacy requirements in 2017 in the form of a regulatory filter. … While the filter was legal, the PInC questions its usefulness. … without the filter, Credit Suisse would have failed to meet capital adequacy requirements – just marginally in 2021 but significantly in 2022. The PInC sees an urgent need for action in the granting of alleviations to systemically important banks.

… The exit scenarios prepared from the outset included those set out in the TBTF rules (liquidation; ELA) and several additional options (TPO; ELA+; takeover). The PInC believes that the most important scenarios were analysed. However, it criticises the fact that not all the authorities involved had the same level of knowledge during this phase, which may have hindered the possibility of taking decisive action at an earlier stage. In particular, the information given to the Federal Council in autumn 2022 should have been more comprehensive. The PInC also considers that the informal meetings initiated by the then finance minister and the Chairman of the SNB’s Governing Board in the autumn of 2022 were of limited use, as they were not sufficiently coordinated within the regular crisis structures. If the PLB had already been in place, the authorities could have intervened in the autumn to restore confidence without the need for emergency legislation. Furthermore, any scope for action was limited by the regulatory filter introduced in 2017.

… Negotiations between Credit Suisse and UBS proved difficult, and the outcome was uncertain. The authorities therefore continued to pursue a number of fallback options in parallel: restructuring of Credit Suisse, temporary public ownership, or even a forced merger as a last resort. It remains unclear which solution would have been adopted if the emergency takeover had failed.

… The emergency legislation was applied in accordance with the law. In view of the acute situation, the PInC understands that an alternative solution with a foreign bank was no longer feasible at that point in time, even if it might have been more advantageous for Switzerland’s competitive position in the longer term. Additionally, the PInC notes that the chosen solution has revealed certain weaknesses in the existing TBTF regulations.

… The PInC acknowledges the achievements of the authorities in March 2023 in preventing a global financial crisis. However, it believes that lessons must be learnt from their handling of the Credit Suisse crisis, especially given that this was the second time the state had to intervene to save a systemically important bank and also due to the fact that Switzerland now has only one remaining global systemically important bank (G-SIB).

… the current TBTF legislation focuses too heavily on Switzerland, particularly in terms of emergency planning, and that the resolution plan for a G-SIB operating internationally from Switzerland must consider international interdependencies. Furthermore, the current TBTF regulations are not designed to deal with a crisis of confidence and overlook some important market indicators. The PInC recommends restricting future easing of capital and liquidity requirements. It also identifies need for action regarding the current rules on audit oversight.

Coordination between the individual authorities and the involvement of the Federal Council as a whole was found to be suboptimal, with particular attention needed in the exchange of information. Improvements are also needed in risk management and early crisis detection.

UBS, now Switzerland’s only G-SIB, is many times larger relative to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) than other financial institutions are relative to their country’s GDP. The PInC considers it essential that this fact be given due consideration in the regulations.

“Governments are bigger than ever. They are also more useless”

Says The Economist. The authors argue that falling state capacity, incompetence, corruption, and transfer/entitlement spending, which crowds out public investment and services, are to blame.

Update: Related, in VoxEU, Martin Larch and Wouter van der Wielen argue that

[g]overnments lamenting a stifling effect of fiscal rules on public investment are often those that have a poor compliance record and, as a result, high debt. They tend to deviate from rules not to increase public investment but to raise other expenditure items.

The New Keynesian Model and Reality

To analyze the transmission from interest rate policies to output and inflation, many academics and central bank economists use the basic New Keynesian (NK) ‘three-equation model’ and its various extensions. A key factor responsible for the model’s success is the seeming alignment with conventional wisdom—some of the model features can be framed in the language of familiar business cycle narratives, as found in newspapers, central bank communication, or introductory macroeconomics courses. But the resemblance between model and narratives is deceptive and the framing misleading. Practitioners and journalists might think that they base their reasoning on the NK model, but typically that’s not what they do.

So, what does the NK model really say? Few writers have identified the model’s fundamental elements more clearly than Stanford’s John Cochrane. In the context of his work on the ‘Fiscal Theory of the Price Level’ (FTPL), which partly overlaps with the NK model, he has thoroughly scrutinized the latter framework and compared it to prevalent views among policy makers and commentators. His verdict is harsh. In a recent blog post he writes:

There is a Standard Doctrine, explained regularly by the Fed, other central banks, and commentators, and economics classes that don’t sweat the equations too hard: The Fed raises interest rates. Higher interest rates slowly lower spending, output, and hence employment … slowly bring down inflation … So, raising interest rates lowers inflation …

The trouble is, standard economic theory, in essentially universal use since the 1990s, including all the models used by central banks, don’t produce anything like this mechanism. We do not have a simple economic theory, vaguely compatible with current institutions, of the Standard Doctrine.

At the heart of the NK model are three equations: One that nearly all macroeconomists take seriously, another one that many consider reasonable, and a final equation that only a few would wholeheartedly endorse. The first equation is the consumption Euler equation. It represents the fundamental concept of choice in the face of scarcity, capturing substitution towards cheaper goods: When the price of apples relative to oranges falls, households consume relatively more apples. The same logic applies with respect to current and future consumption: Higher real interest rates render future relative to current consumption cheaper, i.e., higher real interest rates go hand in hand with stronger growth. Accordingly, a higher nominal interest rate is associated with a strengthening of economic activity unless it triggers an even stronger increase in inflation.

Higher real interest rates make output higher in the future than today, and so raise output growth. The best we can hope [for in terms of reconciling Standard Doctrine and Euler equation] … is to have output jump down instantly today when the interest rate rises.

The second equation, the ‘Phillips curve,’ represents firms’ price setting. It relates current as well as expected future inflation to contemporaneous output. Underlying this second equation is the assumption that firms compete against each other and try to charge a markup over cost. Price increases by other firms as well as higher production, which pushes up costs, induce firms to raise their own prices as soon as they get a chance (sticky prices). But again, this is not easy to reconcile with the ‘Standard Doctrine:’

Again the sign is “wrong.” Suppose the economy does soften, lower [production] … A softer economy means lower inflation … relative to future inflation. It means inflation rises over time. At best, perhaps we can get inflation to jump down immediately, but then inflation still rises over time. … (This is an old puzzle, pointed out by Larry Ball in 1993.)

The final, least credible equation represents an interest rate rule whose coefficients satisfy the ‘Taylor principle.’ The assumption is that the interest rate set by the central bank systematically responds to inflation (and potentially output), and strongly so. The third equation and the ‘Taylor principle’ do not bear resemblance to real-world central banking, although many central bankers and journalists talk about ‘Taylor rules,’ which is not the same as the ‘Taylor principle.’ Rather, the equation and the principle are needed for technical reasons that relate to the dynamic properties of difference equations and more specifically, the number of unstable eigenvalues and jump variables. Paired with the assumption that output and inflation eventually return to their pre-shock trends, the equation subject to the ‘Taylor principle’ forces output and inflation to jump to specific values after the system is shocked.

Cochrane rejects the interest rate rule subject to the ‘Taylor principle’ as bogus. Instead, he favors an ‘FTPL’ mechanism to pin down output and inflation after a shock. According to the ‘FTPL,’ fiscal policy makers set primary surpluses ‘actively,’ i.e., independently of inflation. Inter temporal government budget balance then implies that changes in the economic environment, for instance a change in interest rates, give rise to an equilibrating jump in the aggregate price level, so fiscal policy pins down inflation.

Obviously, I think the fiscal theory story makes a lot more sense. The Fed does not have an “equilibrium selection policy.” The Fed does not deliberately destabilize the economy. The central story of how interest rates lower inflation is that the Fed threatens to blow up the economy in order to get us to jump to a different equilibrium. If you said that out loud, you wouldn’t get invited back to Jackson Hole either, though equations of papers at Jackson Hole say it all the time. The Fed loudly announces that it will stabilize the economy — that if inflation hits 8%, the Fed will do everything in its power to bring inflation back down, not punish us with hyperinflation.

Given the weak conceptual and empirical foundations of the third equation and the ‘Taylor principle,’ Cochrane is right to dispute the conventional argument that inflation is pinned down by this very equation—the Fed’s threat to ‘blow up the economy.’ But the FTPL mechanism he favors relies on a similar threat, in this case by fiscal policy makers. With ‘active’ fiscal policy, inflation is pinned down by the inter temporal government budget balance requirement; unless inflation assumes the ‘right’ value, government debt spirals out of control.

Independently of whether you believe in the third equation of the NK model subject to the ‘Taylor principle’ or in ‘active’ fiscal policy along the lines of the ‘FTPL,’ the implications are stark:

But we don’t have to take sides on that debate, because the result is the same, and the question here is whether current models can reproduce the Standard Doctrine. When interest rates rise, we can have an instantaneous jump down in inflation, that lasts one period before inflation rises again.

But this is a long way from the Standard Doctrine. First, we still have inflation that jumps down instantly and then rises over time, where the Standard Doctrine wants inflation that slowly declines over time. That sign is still wrong.

Second, the jump occurs because, coincidentally, fiscal policy tightened at the same time. Whether that happened independently, by fiscal-monetary coordination, or because the Fed made an equilibrium-selection threat and Congress went along doesn’t matter. Without the tighter fiscal policy you don’t get the lower inflation. So this is not really the effects of monetary policy. At best it is the effect of a joint monetary and fiscal policy.

Moreover, the fiscal/equilibrium selection business is doing all the work. You can get exactly the same unexpected inflation decline (or rise) with no change in interest rate at all. …

The mechanism is also a long way from the Standard Doctrine. The decline in inflation has nothing to do with the higher interest rates. There are no higher real interest rates anyway in this story. There is a fall in aggregate demand, but it comes entirely from tighter fiscal policy, having nothing to do with higher interest rates.

Cochrane is right to argue that the NK model’s transmission from interest rates to output and inflation has fiscal consequences, which the literature typically disregards. Consider the consequences of a shock. If we insist on the third equation subject to the ‘Taylor principle,’ then the inflation jump that guarantees stable system dynamics implies a revaluation of outstanding nominal debt (if there is some), which in turn requires fiscal policy makers to adjust future primary surpluses. So, the standard model subject to the ‘Taylor principle’—the Fed’s threat to blow up the world—implies that a shock to the interest rate (a ‘monetary policy shock’) forces fiscal responses. Cochrane asks, why researchers do not pay more attention to the fiscal consequences of ‘monetary policy shocks,’ and why they interpret the output and inflation dynamics resulting from the shock as the effects of monetary rather than monetary-and-fiscal policy.

If we instead dump the third equation and replace it with the notion of ‘active’ fiscal policy, then the shock cannot change future primary surpluses. Now, the inter temporal government budget balance requirement joint with the predetermined level of nominal debt (if some is outstanding) pins down contemporaneous inflation. And according to Cochrane, the traditional output and inflation adjustment paths to the ‘monetary policy shock’ are gone.

Cochrane discusses how the problems of the NK model transcend that model—they are not a consequence of the price stickiness assumption, i.e., the ‘Phillips curve.’ Even without price stickiness, the dynamics according to the ‘Standard Doctrine’ are hard for the Euler equation and the third equation to match.

The only way to get inflation and output to decline at all is to pair the interest rate rise with a FTPL fiscal shock or a multiple-equilibrium-selection-threat by the Fed, which induces a fiscal shock. Even then, we still get inflation that jumps down and then rises, and has nothing to do with the mechanism of the Standard Doctrine. The fiscal shock or equilibrium-selection threat is still coincidental with raising interest rates, and indeed has to fight the fact that higher interest rates want to raise inflation.

Cochrane suggests long-term debt as a potential model ingredient to better align model predictions under the ‘FTPL’ approach with the data. He also speculates why the NK model has been so successful in academia and central banks in spite of its dubious mechanics:

How could this state of affairs have gone on so long, that the basic textbook model produces the opposite sign from what everyone thinks is true, for 30 years? Well, interpreting equations is hard.

This paper contains more discussion and analysis. Have a look yourself and be prepared for a new business cycle framework.

Urban Roadway in America: Land Value

In a CEPR discussion paper, Erick Guerra, Gilles Duranton, and Xinyu Ma estimate the cost of land use for roads in the U.S.

“Macroeconomics II,” Bern, Fall 2024

MA course at the University of Bern.

Time: Monday 10:15-12:00. Location: A-126 UniS. Uni Bern’s official course page. Course assistant: Stefano Corbellini.

The course introduces Master students to modern macroeconomic theory. Building on the analysis of the consumption-saving tradeoff and on concepts from general equilibrium theory, the course covers workhorse general equilibrium models of modern macroeconomics, including the representative agent framework, the overlapping generations model, and the Lucas tree model.

Lectures follow chapters 1–4 (possibly 5) in this book.

“Makroökonomie I (Macroeconomics I),” Bern, Fall 2024

BA course at the University of Bern, taught in German.

Time: Monday 14:15-16:00. Location: Audimax. Uni Bern’s official course page. Course assistant: Sally Dubach.

Course description:

Die Vorlesung vermittelt einen ersten Einblick in die moderne Makroökonomie. Sie baut auf der Veranstaltung „Einführung in die Makroökonomie“ des Einführungsstudiums auf und betont sowohl die Mikrofundierung als auch dynamische Aspekte. Das heisst, sie interpretiert makroökonomische Entwicklungen als das Ergebnis zielgerichteten individuellen (mikroökonomischen) Handelns, und sie wird der Tatsache gerecht, dass wirtschaftliche Entscheidungen Erwartungen widerspiegeln und Konsequenzen in der Zukunft haben. Der klassische Modellrahmen, der in der Vorlesung entwickelt wird, bietet die Grundlage für die Analyse von Wachstum, Konsum, Arbeitsangebot, Investitionen oder Geld- und Fiskalpolitik sowie vieler anderer Themen, die auch in anderen Veranstaltungen des BA Studiums und darüber hinaus behandelt werden.

The course closely follows Pablo Kurlat’s (2020) textbook A Course in Modern Macroeconomics (book website). Lecture notes are available here. The following sections in the lecture notes are not covered in class and are not relevant for the exam:

- Last pages of chapter 7, starting at p. 106;

- last pages of chapter 9, starting at p. 128;

- chapters B and C.

“Money and Banking with Reserves and CBDC,” JF, 2024

Journal of Finance. HTML (local copy).

Abstract:

We analyze the role of retail central bank digital currency (CBDC) and reserves when banks exert deposit market power and liquidity transformation entails externalities. Optimal monetary architecture minimizes the social costs of liquidity provision and optimal monetary policy follows modified Friedman rules. Interest rates on reserves and CBDC should differ. Calibrations robustly suggest that CBDC provides liquidity more efficiently than deposits unless the central bank must refinance banks and this is very costly. Accordingly, the optimal share of CBDC in payments tends to exceed that of deposits.

A Financial System Built on Bail-Outs?

In a Wall Street Journal opinion piece and an accompanying paper and blog post, John Cochrane and Amit Seru argue that vested interests prevent change towards a simpler, better-working financial system. They describe various “bail-outs” since 2020, in the U.S. financial sector and elsewhere. They point out that in Switzerland, too, the government orchestrated takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS relied on taxpayer support. And they conclude that regulatory measures after the great financial crisis including the implementation of the Dodd-Frank act failed. Instead, Cochrane and Seru favor narrow banking (they prefer to call it “equity-financed banking and narrow deposit-taking”):

Our basic financial regulatory architecture allows a fragile and highly leveraged financial system but counts on regulators and complex rules to spot and contain risk. That basic architecture has suffered an institutional failure. And nobody has the decency to apologize, to investigate, to talk about constraining incentives, or even to promise “never again.” The institutions pat themselves on the back for saving the world. They want to expand the complex rule book with the “Basel 3 endgame” having nothing to do with recent failures, regulate a fanciful “climate risk to the financial system,” and bail out even more next time.

But the government’s ability to borrow or print money without inflation is finite, as we have recently seen. When the next crisis comes, the U.S. may simply be unable to bail out an even more fragile financial system.

The solution is straightforward. Risky bank investments must be financed by equity and long-term debt, as they are in the private credit market. Deposits must be funneled narrowly to reserves or short-term Treasurys. Then banks can’t fail or suffer runs. All of this can be done without government regulation to assess asset risk. We’ve understood this system for a century. The standard objections have been answered. The Fed could simply stop blocking run-proof institutions from emerging, as it did with its recent denial of the Narrow Bank’s request for a master account.

Dodd-Frank’s promise to end bailouts has failed. Inflation shows us that the government is near its limit to borrow or print money to fund bailouts. Fortunately, plans for a bailout-free financial system are sitting on the shelf. They need only the will to overcome the powerful interests that benefit from the current system.

Budgetary Effects of Ageing and Climate Policies in Switzerland

A report by the Federal Finance Administration anticipates lower net revenues for all levels of government.

… demographic-related expenditure will increase from 17.2% of gross domestic product (GDP) to 19.8% of GDP by 2060. If no reforms are made, public debt would rise from the current 27% to 48% of GDP. The need for reform is particularly pronounced at federal (including social security) and cantonal level. While AHV expenditure in particular poses a challenge for the Confederation, especially after the adoption of the popular initiative for a 13th AHV pension payment, cantonal finances are coming under greater pressure, particularly in terms of healthcare expenditure.

… the path to net zero will primarily place a financial burden on the federal government and the social security funds. This is because climate protection measures dampen economic growth and thus also the growth in public receipts. The electrification of the transport sector will also lead to a loss of revenue from mineral oil tax and the performance-related heavy vehicle charge (LSVA). However, the study assumes that these can be offset by replacement levies. Greater use of subsidies in the climate policy will further increase the pressure on public finances. In 2060, depending on the policy scenario, the general government debt ratio would be 8% to 11% higher than without climate protection measures. Although no robust international or Swiss estimates are yet available, scientists agree that the costs of climate change for public finances will be significantly higher than the costs of climate protection measures.

SNB Annual Report

The SNB has published its annual report. Some highlights from the summary:

Climate risks and adjustments to climate policy can trigger or amplify market fluctuations and influence the attractiveness of investments. From an investment perspective, such risks are essentially no different from other financial risks. The SNB manages the risks to its investments by means of its diversification strategy. …

A prerequisite for illiquid assets to be used as collateral in obtaining liquidity assistance is that a valid and enforceable security interest in favour of the SNB can be established on these assets. Otherwise, should the loan not be repaid, the SNB would be unable to realise the collateral. A decisive factor for the usability of assets is that the banks have made the necessary preparations. …

The crisis at Credit Suisse highlighted weaknesses in the regulatory framework. Banks’ resilience and their resolvability in a crisis should therefore be strengthened. At the same time, the current ‘too big to fail’ (TBTF) regulations should be reviewed to ensure that they take adequate account of the systemic importance of individual banks. In particular, the SNB recognises a need for action in the areas of early intervention, capital and liquidity requirements, and resolution planning. It is participating at both national and international level in the ongoing debate about regulatory adjustments.

In 2023, the SNB presented its ‘Liquidity against Mortgage Collateral’ (LAMC) initiative to the public. Banks of all sizes can find themselves in a situation where they need significant amounts of liquidity quickly despite having precautions in place that comply with regulations. The aim of the LAMC initiative is to ensure that, should the need arise, the SNB will in future be able to provide liquidity against mortgage collateral to all banks in Switzerland that have made the requisite preparations. This possibility was already available to systemically important banks. Preparatory work for this initiative started in 2019. …

Employees from the BIS and the SNB continued their research activities at the BIS Innovation Hub Swiss Centre. Work focused on technologies for tokenising assets and on the analysis of large volumes of data. …

At the invitation of the Indian G20 presidency, Switzerland again participated in the Finance Track in 2023. In this forum, the SNB emphasised the importance of pursuing a monetary policy geared towards price stability and contributed its analyses of central bank digital currency and payment systems. …

The SNB introduced a new current account survey in order to better record the global production of multinational enterprises whose production and trade processes are distributed across various countries in Switzerland’s balance of payments statistics.

Banks and Privacy, U.S. vs Canada

JP Koning writes:

An interesting side point here is that Canadians don’t forfeit their privacy rights by giving up their personal information to third-parties, like banks. We have a reasonable expectation of privacy with respect to the information we give to our bank, and thus our bank account information is afforded a degree of protection under Section 8 of the Charter.

My American readers may find this latter feature odd, given that U.S. law stipulates the opposite, that Americans have no reasonable expectation of privacy in the information they provide to third parties, including banks, and thus one’s personal bank account information isn’t extended the U.S. Constitution’s search and seizure protections. This is known as the third-party doctrine, and it doesn’t extend north of the border.